Massimo Polidoro

Curse That Painting! Notes on a strange world

(Skeptikal Inquirer, vol. 36.6, November /December 2012).

Paranormal legends about paintings have always existed. Some think that a picture falling off the wall represents a bad omen for the person depicted or photographed in it. Others feel watched by some portraits whose eyes seem to follow onlookers as they move through a room. And still others claim that paintings can come alive; people in it can move, smile, close their eyes, or even leave the picture. And, of course, tales of “cursed” paintings abound.

Certainly great writers, from Oscar Wilde with The Picture of Dorian Gray to Stephen King with Rose Madder, have been able to tell extraordinary stories of scary and unsettling paintings. However, many believe that “haunted” paintings can exist in real life. Coming from a family that has always dealt with paintings—my grandfather is a painter, my father was an art collector, and together with their wives they have run a shop selling paintings for over fifty years—it is easy to understand why this is a subject that particularly fascinates me.

| The Hands Resist Him |

|

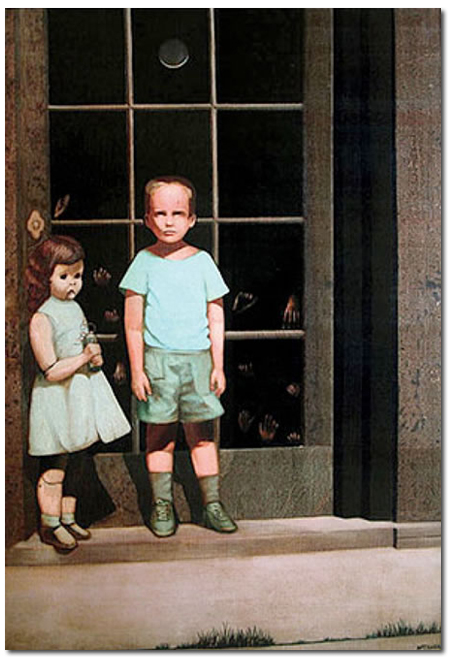

The Hands Resist Him painting by Bill Stoneham was sold on eBay as “cursed.” |

In February 2000, a supposedly cursed painting was auctioned on eBay. It was titled The Hands Resist Him and was painted in 1972 by California artist Bill Stoneham. It depicted a young boy and a female doll standing in front of a glass paneled door against which many hands are pressed. The owners claimed that the characters in it came alive, sometimes leaving the painting and entering the room in which it was being displayed. It was sold for $1,025 to Perception Gallery in Grand Rapids, Michigan, which, when contacted some time later, stated that they had not noticed anything strange since buying the painting.

Luckily for Stoneham, the rumor caused by the story made the painting so popular that it was depicted in a short movie by A.D. Calvo (Sitter), as the CD cover art for Carnival Divine’s self-titled album, and was featured in the PC video game “Scratches.” Today, prints of it—and of its sequel, Resistance at the Threshold—are sold in different sizes.

Smiling Portrait |

|

Portrait of Teresa Rovere. On the right, seen through a viewfinder, the face seems to smile; it’s just an illusion created by the shape of the lens. |

In November 2005, the Italian TV show Voyager showed a painting owned by self-proclaimed psychic Gustavo Rol from Turin. It depicted a noble lady, Teresa Rovere, wearing nineteenth century garments and a somber frown. However, when the painting was seen through the viewfinder of a camera the mouth seemed to curl upward, forming a smile. Nothing could be seen with the naked eye and the film recorded through the camera did not show anything unusual. On the show, it was claimed that this was an unexplainable phenomenon, maybe an after-life paranormal experiment of the late Rol. In reality, it was a simple optical effect due to the round shape of the viewfinder, the lens of which tends to narrow and make rounder anything seen through it: thus, the coronet on Teresa’s hair seems to bend downward just like the mouth appears to bend upward, creating the illusion of a smile that in reality is not there.

Tears for Fears |

|

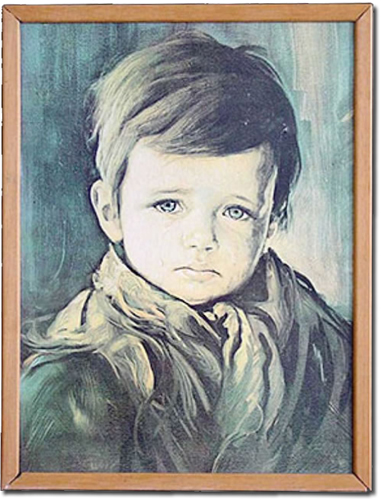

One of the many replicas of the Crying Boy painting. |

The most bizarre and enduring story of all is certainly the “Curse of the Crying Boy,” a story told in an article by David Clarke published in Fortean Times (July 2008). It all started on September 4, 1985, when British tabloid newspaper The Sun published an article titled “Blazing Curse of the Crying Boy.” It told of a couple who blamed a cheap painting of a child with big tears on his cheek for a fire that destroyed their house in Rotherham, South Yorkshire. The fire broke out from a pan in the kitchen and spread rapidly. However, the framed print of the Crying Boy remained on the wall unscathed.

What made this mundane episode national news was the statement of a local firefighter who said that he knew of numerous other cases where prints of the Crying Boy had turned up, undamaged, in the ruins of homes destroyed by fire. The Sun was soon inundated by letters telling of similar episodes and a background story for the painting was soon established. First of all, not all paintings were identical. They all were kitschy prints of crying kids, sold in tens of thousands of copies in branches of British department stores during the 1960s and 1970s.

|

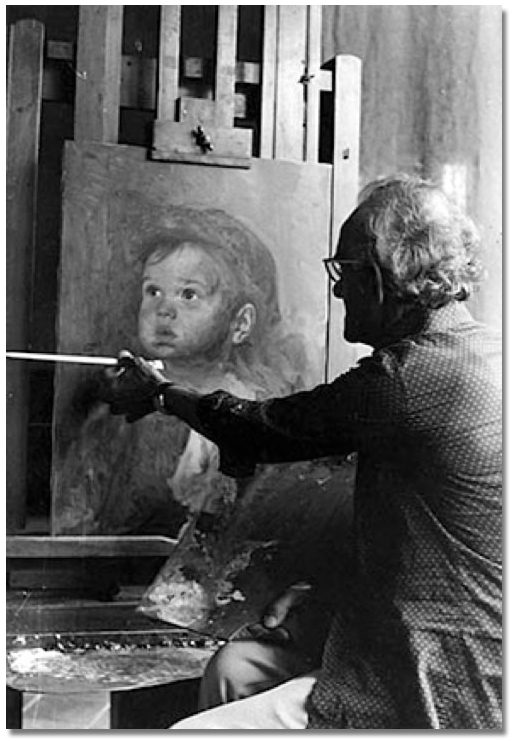

A very rare image of Bruno Amadio painting a Crying Boy in his studio. (Photo © 2012 Massimo Polidoro) |

The original painting that started the whole scare was signed G. Bragolin, which The Sun claimed was “an Italian artist.” Others stated that Giovanni Bragolin was the pseudonym of a Spanish painter, Bruno Amodio, also known as “Franchot Seville.” Clarke reports that attempts to trace the man floundered as art historians said he did not appear to have a “coherent biography.” Roy Vickery, the secretary of a British Folklore Society, was quoted by The Sun to the effect that the original artist might have mistreated the child model in some way, adding: “All these fires could be the child’s curse, his way of getting revenge.”

The hysteria grew so wide that the South Yorkshire Fire Service issued a statement dismissing the connection between the fires and the prints. It explained that the most recent blaze was started by an electric heater left too close to a bed. “Fires are not started by pictures or coincidence,” stated Chief Divisional Officer Mick Riley, “but by careless acts and omissions. The reason why this picture has not always been destroyed in the fire is because it is printed on high-density hardboard, which is very difficult to ignite.” A bonfire of 2,500 copies of such paintings was even staged by The Sun in an attempt to milk every last drop of sensationalism from the news story. After that, the number of tabloid stories began to fade, but the “curse” transformed itself on the Internet into a modern urban legend.

The Legend of El Diablo

Today many people claim that if you treat the paintings well they bring good luck, while others say that if you hang close together the paintings of a crying boy and of a crying girl the house will be protected by any possible danger.

In the end, “a well respected researcher into occult matters, a retired schoolmaster from Devon named George Mallory,” was said in the Clarke article to have discovered the origins of the paintings. Mallory had been able to trace the actual artist who had painted the original, Franchot Seville (it was him, then, who used as pseudonyms both Bruno Amodio and G. Bragolin). Seville explained that in 1969 he had found a little street boy wandering around Madrid. The child never spoke and had very sad eyes. Seville decided to paint him, and a Catholic priest, looking at the painting, identified him as Don Bonillo, a child who had run away after seeing his parents die in a blaze. The priest then warned Seville to stay away from Bonillo for wherever he went mysterious fires would break out: the villagers even called him “El Diablo” because of this. Seville ignored him and adopted the boy, using him as his constant model. The paintings sold well but when the studio was destroyed by a fire, the painter accused the child of arson. Bonillo ran away and was never seen again. Only many years later the victim of a car crash was identified as nineteen-year-old Don Bonillo.

In fact, no one named George Mallory, Franchot Seville, or Don Bonillo ever existed. But it doesn’t matter, the legend of the curse of the Crying Boy is alive and well, just like the paintings that would not die.

The Real Life Painter

In the winter of 2009, I was finally able, by chance, to trace the real artist who had painted the Crying Boy series. He was Italian and his name was Bruno Amadio (not “Amodio”). His neighbor Antonio Casellato of Trebaseleghe, near Padua, read an article I wrote about this story in an Italian magazine and sent me a letter. “I knew Amadio very well. I lived in the house next to him for ten years and after his death I have bought his home and all that was in it.”

I called Casellato and learned more about Amadio. “He was a marvelous person, always smiling and kind,” Casellato told me.

He was a true artist and taught at the Academy of Venice. His painting style was of very high quality. I own many of his paintings and they are beautiful. That’s why I am sorry that he is remembered just for the Crying Boys. That was something that he painted just because it sold well [today original copies of Crying Boys can reach $3,500]: as good as an artist may be, it is very rare that he can live in affluence. So, since they kept asking him for those paintings from all over the world, he obliged and painted them. But he did so reluctantly, that’s why he used a pseudonym, “Bragolin.” Do you want to know were that name came from? His uncle, who had worked in vaudeville, used it and had given him permission to adopt it. |

In 1981, at age seventy-three, Amadio died of disease of the esophagus and the legends broke out. “Some time ago,” added Casellato, “a Swedish journalist came here. He was interested in filming a documentary. He was convinced that Amadio had been a poor child and that he always painted the same subject in the hope to save other children from poverty. He went away depressed when I told him the truth. That’s all; I just wanted to say that Bruno Amadio was a real person and not the fictional character of some unlikely urban legend.”

|

A “non-crying boy” painting by Amadio: Pumpkins. (Photo © 2012: Massimo Polidoro) |